Welcome to the Museum of Computational Architectures at the University of Naples Parthenope

This museum showcases the history of computing through “artifacts” of significant historical value. We will explore how computational architectures have evolved over the years with the goal and aid of miniaturization: utilizing all available space… but reducing it as much as possible.

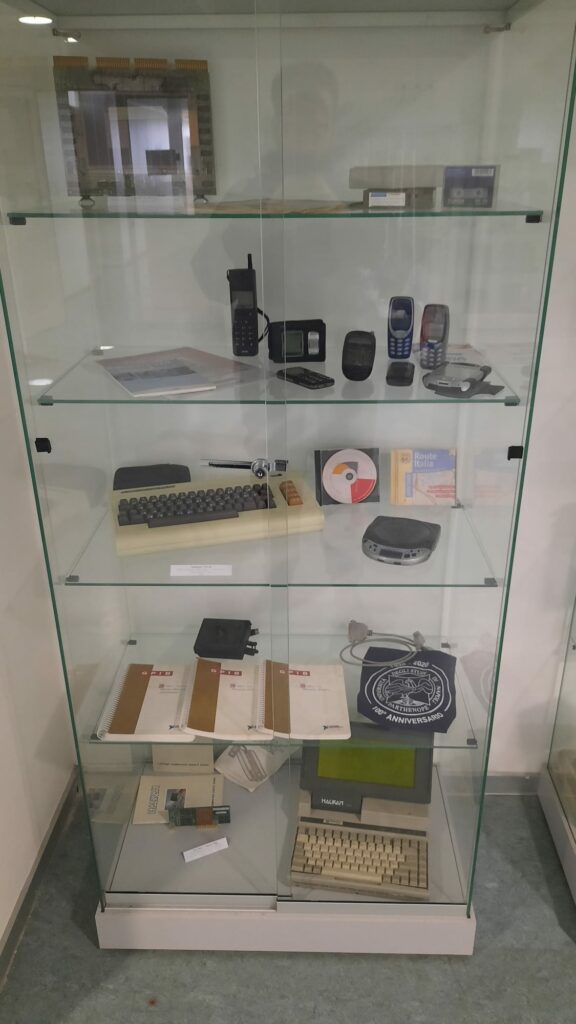

Cabinet A3

Our journey begins with a glance at both the past and the future. The first hardware component we will see is located at the bottom of the first shelf: a ferrite core memory RAM.

A RAM using this technology was widely used and played a significant role in the evolution of computational architectures. How did it work? Imagine two semicircular magnets placed perpendicularly to each other, with electric cables running through them. In this way, depending on the voltage passing through the cables, a magnetic field could be generated, allowing the storage of a single bit (0 or 1). However, it had a crucial characteristic: when data was read, it was erased from the memory.

If you notice a series of red dots along the entire board, good! Those are the ferrite cores mentioned earlier.

Looking towards the future, right in front of our ferrite core RAM, we find a Blue Gene P computational node used in high-performance computing environments. Observe the size difference: the RAM at the back is much larger than the computational node, and furthermore, the RAM, despite its large size, was used in a single-processor environment compared to the computational node. Between the 1970s (when the first ferrite core RAMs were developed) and 2007 (when the computational node dates back to), we can observe the significant evolution of computing devices.

If today we can post on Instagram about our daily lives or create content on TikTok, it’s thanks to the evolution of mobile technology: portable or “pocket-sized” computing devices.

On the second shelf, we find the progression of mobile phones over time: from the 1990s with the Nec P7 and Motorola D160, up to the Motorola C113a from 2005, passing through the famous Nokia 3210 from 1999. Although far from today’s cell phones, they were a major innovation and an important step toward the devices we have now.

Staying on the topic of pocket-sized devices, we can also notice two other very interesting gadgets: a Compaq iPAQ palm (or “portable PC”) from 2001, and a slightly younger Acer MP3 player (2005).

Today’s laptops are very thin, light, and designed for convenience. In the distant 1980s, the first laptops were born, quite different from those we know today. We can see two portable computers (even before they were called laptops) that look much heavier and bulkier than modern ones: the Amstrad PC1640 and the HALiKAN LX-20. But the portable computer section doesn’t end here because, on the third shelf, there is the famous Commodore VIC-20 from 1982: an all-in-one computer that only needed a power connection and a monitor to work!

Cabinet A2

If you’re wondering how files and data are stored on your devices, the answer to your question lies on the first shelf: hard drives. Hard drives are permanent storage devices based on magnetic disk technology. These disks spin at very high speeds, and that mechanical arm you see reads and writes data on the disk using the phenomenon of magnetism. Next to it, you can see the back of a hard drive, or the controller: a hardware device that allows the operating system to interface with the actual magnetic disk.

On the second shelf, we can see the “ancestors” of hard drives: floppy disks. They were also permanent storage devices that used magnetism to store data. Instead of a disk, floppy disks used magnetic tape, and their capacity was very limited: they could hold data in the order of KB or MB, compared to their successors (the hard drives) that now store data in the order of GB or TB.

Notice again the size: floppy disks were much larger compared to the first hard drives and even more so compared to modern hard drives.

What you see on the far left of the shelf is an internal floppy disk drive (there’s also a portable floppy disk drive in the case on the other side!).

On the third shelf, we can spot an entire operating system kit on disk: DOS, which was very famous and widely used in 1992, but later surpassed by the renowned Microsoft Windows 95 (two user manuals for this system are also displayed on the shelf).

If you’ve ever wondered what Intel Pentium II and III processors looked like, you can see them on the third shelf as well, dated 1997 and 1999.

We decided to put the lion and the tiger in the same cage, two sworn enemies sharing the same shelf: Intel and AMD, in particular, two motherboards for 8086 processors, respectively on the left and right.

Videogames Section

In this section of the MARC, we will observe how computing has evolved from the industrial and home computer sectors into the realm of entertainment: video games.

Before diving into the world of gaming, it’s essential to focus on the data storage section. This includes floppy disks, floppy disk drives, magnetic tapes, and various interfaces used to connect storage devices. The floppy disk is a magnetic medium that dominated the market for a long time due to its compact size. It consists of a small plastic case with a thin magnetic disk inside. The floppy disk was inspired by magnetic tape storage, those large reels of tape. The revolution was the creation of removable floppy disk drives, which could be connected to the computers of that era using a serial interface.

Next, we have the network connectivity section. Here, we have networking devices from the 1990s, particularly the DECrepeater90C, a network repeater used in early Ethernet networks, which utilized coaxial connections and a serial port. Additionally, there is the DECBridge 90FL, a network device that was installed in computers to connect them to a LAN (today’s equivalent of an Ethernet network interface).

One standout item is the NVIDIA Tesla graphics card. Notice that it has no output ports because it is used exclusively for parallel computations. It is typically employed to train neural networks within computing environments consisting of other graphics cards.

Another interesting observation is the presence of several laptops that are very similar in design to modern ones, even though they date back to the 1980s and 1990s. This shows that ease of use transcends time.

In the video game industry, technology has progressed significantly, improving performance (more powerful consoles), graphics (games that look realistic), and especially immersion (VR headsets). The most notable and famous item is the SEGA Master System console from 1980. It has serial connectors for control pads, and the games were on cartridges. These cartridges consist of a plastic case with a PCB board inside, containing various memory chips that hold the game’s ROM.

A device that showcases the early stages of immersive gameplay is the Sega Light Phaser. This is a gun-shaped controller that connects to the console via a serial interface. It works on the principle of a photodiode: when the gun is pointed at the TV and the trigger is pulled, the screen goes black for a brief moment, and only the game elements that can be hit remain lit. Each element has a different color intensity, so the photodiode at the tip of the gun transmits to the console the color detected (i.e., the object or enemy being shot). Over time, controllers evolved to enhance immersion, from joysticks—like the ones on display in the MARC—to modern joypads like those for the Nintendo Wii or various PlayStation consoles.

Special mention goes to our Lamborghini pedal steering wheel. Despite being produced in 1981, its design is identical to those used today. What has changed is not so much the software or sensor components but the mechanical aspects. This is again related to immersion: the steering mechanics have been improved, becoming heavier yet lighter to steer, with a feel closer to real car steering wheels. The pedal set is also heavier and more realistic… sometimes it’s not the computing itself that evolves, but the technology surrounding it.

We also have the famous Apple Macintosh Plus, one of the first Apple computers, part of the original series. This was a revolution for computers at the time because the components were sold separately, so it was up to the customer to assemble and operate them. In fact, we also have user manuals for other computers that guide the user through assembly and troubleshooting common issues. What happened if there was a problem not covered in the manuals? During those years, specialized weekly magazines were sold, offering solutions to problems that emerged after the sale.

The experience in the MARC’s video game section concludes with floppy disk video games for Windows PCs and the first Xbox console. These disks contained the entire game, similar to the cartridges of the SEGA Master System. When discussing video games, piracy must also be mentioned, as it has always existed, whether with game cartridges or disks. Unfortunately, piracy cannot be entirely eradicated, but manufacturers protected their products using various methods: cartridges often included security chips that performed checks when the game was launched, or players were asked to input a code provided with the cartridge, like a password to play. On the other hand, disks were often protected using copy-prevention technologies (disk encryption or various techniques that prevented DVD drives from making copies). Today, physical game copies on disks still exist, but they often contain only part of the game and an activation key. To play, you must download the rest of the game from the internet using the key provided in the package (this applies to both PC and console games).